http://www.bakersfield.com/news/2009/10/28/lois-henry-fight-for-the-kern-river-begins.html

The best thing about the state water hearing on whether there’s unclaimed water in the Kern River that we might be able to use for an actual river is that it’s over.

I swear, I don’t know which is worse — deadly dull water law or the lawyers who wallow in it.

Anyway, besides me, there were only two other “civilians” attending the State Water Resources Control Board Kern River hearing held Monday and Tuesday.

The others were hardy Bakersfield couple Doug Worley and Cathy Barnes sporting matching “Bakersfield: A riverbed runs through it” T-shirts.

“We came up to support Bakersfield having a river, ” Worley said. “Half the town should have come up for this.”

They followed every arcane twist and complex turn in the hearing, cheering on Bakersfield’s attorney, Colin Pearce, as he dueled with no fewer than five attorneys from the opposition who represented four powerhouse ag districts and the city of Shafter.

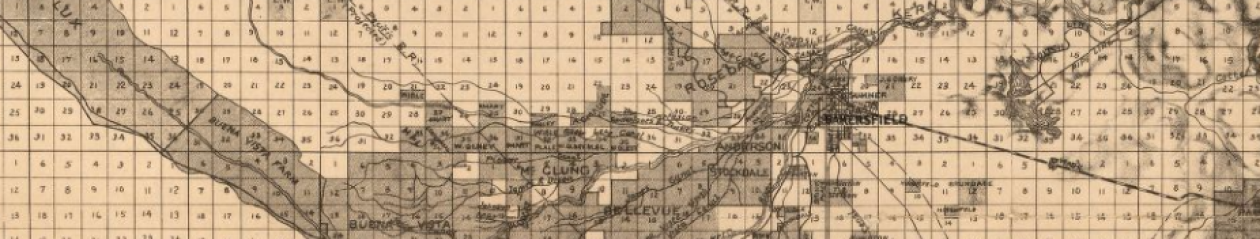

For a little background, the city petitioned the state board to find there is unclaimed water in the Kern after a 2007 court ruling held that Kern Delta Water District had forfeited some of its rights to the river. The city wants that water, possibly as much as 50,000 acre-feet a year, to run down the river.

The opposition (North Kern Water Storage District, Buena Vista Water Storage District, Kern Water Bank Authority, Kern County Water Agency and Shafter) want the board to find there is no unclaimed water.

It’s the same “nothing to see here, move along” attitude that has long governed use of the Kern.

It’s interesting to note that initially all those districts and Shafter had also asked the board to find there was excess water on the river and each also petitioned to have it given to them. They changed tactics for some reason, however, and joined forces to oppose the city and try to dissuade the board from even considering the issue.

Despite their best efforts, the state board granted the hearing in near-record time. This first phase is only to determine if there is water available.

Board member Arthur Baggett Jr., who acted as the hearing officer, told me he expects to make his recommendation to the full board before the end of the year. If the board finds there is unappropriated water, that’s when the real fighting starts.

“Then everyone gets a shot at it, ” Baggett, a silver-haired Mariposa lawyer who looks more like a Wyatt Earp stand-in complete with black boots and vest, told me.

But don’t hold your breath. Baggett also told me the board just issued the final water right last week on the Santa Ana River, a similar case that came to them 11 years ago.

Ugh.

After watching this week’s hearing, though, I can’t help but have some hope. Because if this was the opposition’s “shock-and-awe” campaign, it was shockingly unawesome.

Their case that the forfeiture didn’t create excess water rests on the idea that the other rights-holders on the river can and have absorbed that water.

After a long series of questions for former city Water Resources Manager Gene Bogart about how he tracked which district got how much water from the Kern on a daily basis, Buena Vista’s attorney Gene McMurtrey smirked triumphantly.

“So, essentially, there’s always been a cap, hasn’t there? And the river has always operated the same way,” he said.

His point was that Kern Delta’s forfeiture didn’t create any new water because so many other “buckets” are waiting to be filled down the line.

Interesting theory.

Except those other bucket holders don’t have a right to that water — it’s not theirs. Their rights don’t expand just because Kern Delta’s contracted.

As for the river still operating the same after the 2007 judgment, yes, that’s because the city is waiting for the state board to determine what should be done with that water. Duh!

Either way, it’s in the state board’s hands now.

The really curious thing is why all these districts have closed ranks on this issue.

The water in question is so-called “first point” water. There are only three first point rights-holders including North Kern, Kern Delta and Bakersfield. So if the state board finds some of that water is unclaimed, there’s a strong legal precedent for keeping it in the first-point family rather than letting it go down the river to “second point” or “lower river” rights holders.

You don’t think those districts and Shafter have agreed among themselves to push back on the state in order to dummy up and take the excess water without entitlement, do you? That would be so, so wrong!

If you think things can’t get that cloak and dagger on the Kern, you’d be wrong. Bogart himself spent four years working in a windowless room with no phone built specifically for him and his precious Kern River flow and diversion records when he worked for Tenneco, before the city bought out its rights, and the city was suing for information contained in those records.

“Don’t talk to anyone, ” were his marching orders back then. Apparently some in the water world would like to keep it that way.

These are Lois Henry’s opinions and not necessarily those of The Californian.