Ancient rock art evokes mystery, reverence – even some controversy

LINK to original article: http://www.bakersfield.com/entertainment/ancient-rock-art-evokes-mystery-reverence—even-some/article_999b8a43-d497-592c-98a5-e72683d714b1.html

- BY LOIS HENRY lhenry@bakersfield.com

I’ve toured the Little Petroglyph Canyon on the China Lake Navy base twice now.

Both times, I’ve had the same question as I wandered along the sandy floor looking up at countless images painstakingly chipped into the rocky walls:

Why?

The petroglyphs, considered the largest concentration of Native American rock art in the Western Hemisphere, were carved thousands of years ago.

Some may be 6,000 years old. Others are even older — dating back 10,000, perhaps even 15,000 years.

But certainly it was before electricity and takeout food.

My point is that life was tough back then. You had to expend a lot of energy just to survive.

So why would people take time away from finding food and shelter to make thousands upon thousands of cryptic images on rocks?

The fun and kind of frustrating part about the tour is no one gives you an answer.

Because not only do we not know when the petroglyphs were made, we don’t know exactly who made them.

“The ancient ones” is the only description given during an orientation film at the first stop tour guests make, in Ridgecrest at the Maturango Museum, which hosts the tours.

According to archeologists, the Paiute-Shoshone people settled in the Coso Mountain area about 800 years ago and likely contributed to the rock art.

But scholars argue over whether the majority of the images predate the Paiute-Shoshone.

Either way, current tribal members consider the art sacred and an important part of their heritage.

The bigger mystery, to me, is what the images meant to those who made them.

Even the seemingly self-explanatory carvings, such as bighorn sheep, probably meant more than what they seem on the surface, according to scholars.

The sheep, which used to be prolific in the area, are carved on nearly every surface in the canyon.

Some are clearly being speared, so perhaps those markings depict a recent hunt or wishes for a good hunt.

Others are just there, repeated over and over, leading some scholars to theorize they were spirit animals, possibly associated with water or rain.

Which is interesting because the climate changed in that area dramatically between 12,000 and 700 years ago, going from a lush region with huge lakes (China Lake) to the desert we know today.

So if the petroglyphs were made in the more distant past, those artists were reflecting a very different world, putting their meaning even further out of reach.

People who study these things believe the canyon was a religious site and that shaman or those on spirit quests made the images. Though, again, that’s up for debate.

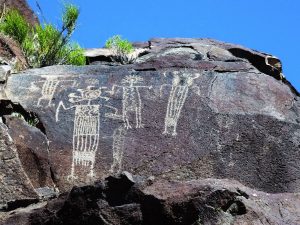

Some images are easily recognizable: the sheep, antelope, weapons, stick-figure humans.

Others are really mysterious, especially the human-like images that scholars say are shaman figures.

Those have long, rectangular bodies filled with geometric designs and bird claw feet sticking out the bottom.

Their heads are sometimes just swirls or seem to be erupting in flames or aren’t heads at all but a pair of eyeballs on the shoulders.

Some appear to be holding daggers. One looks as if it’s stirring a large pot.

Were they depictions of dreams? Visions? Were they meant to convey a ritual or a final step in some kind of training?

At first, they seem fun, whimsical. But the more you look at them, the eerier they become. You get the feeling they were never meant for public consumption.

None of the petroglyphs appears haphazard, as if doodled out of boredom. (I’m not counting the more recent additions such as “J.P.” or “E=MC2”; those are just vandalism.)

The ancient petroglyphs are very detailed and clearly took time to make.

Regardless of their specific meanings, I suppose what the petroglyphs tell us in general is that artistic expression has always been a vital part of human existence no matter how hard that existence might have been.

At least that’s my very unscholarly take.

Rock art: overexposed, underappreciated?

Though the Paiute-Shoshone people haven’t objected to museum-led tours of the petroglyphs, the recent Petroglyph Festival in Ridgecrest has created some bad feelings.

The festival is the latest attempt by the City of Ridgecrest to boost its economy outside of the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, the town’s main employer.

The city has long billed itself as the gateway to Death Valley and has had a trickle of tourism from that. But mostly pass through.

A couple of years ago, it tried a balloon festival. High winds wreaked havoc on that idea, and the balloons.

Then in 2014, city officials held the first petroglyph festival, a joint effort between the Ridgecrest Area Convention and Visitors Bureau and the Maturango Museum.

It was a hit.

Up to 15,000 people flocked to the desert town over the two days of the event, held in early November. (This year’s festival will be Nov. 5-6, http://rpfestival.com/.)

But many Paiute-Shoshone were dismayed that an event promoting a very special and sacred part of their heritage didn’t include them.

In fact, no one from the festival reached out to the Paiute-Shoshone, said Kathy Bancroft, cultural officer of the Paiute-Shoshone in Bishop.

“Even after the festival got some bad publicity over it, no one reached out to the local tribes,” Bancroft said. “It’s very frustrating.”

Instead of Paiute-Shoshone speakers, displays or historical discussions, the festival features a car show, beer garden, tchotchke galore and life-size petroglyph cutouts that people can stick their heads through for photos.

Then there’s the “intertribal” pow-wow with a Cherokee hog fry and Cherokee dances.

The Cherokee weren’t in the Ridgecrest area at the time the petroglyphs were made — or for thousands of years afterward. They have nothing to do with the petroglyphs, Bancroft said.

“It’s insulting. The whole thing just feels like exploitation for profit.”

She and other tribal members would like to see the festival focus on education, especially preservation. Because ancient petroglyphs and pictographs are being damaged, even stolen, throughout the Mojave desert.

Little Petroglyph Canyon on the Navy base is an incredible collection of carvings in one small area. But Bancroft said there are countless more ancient carvings and paintings scattered throughout the desert on open land.

A thorough discussion of the danger those artifacts face would be helpful in raising awareness.

“It’s really strange to me because people come here from around the world because of the petroglyphs. I would think they (festival organizers) would want to teach them the value of the petroglyphs and the meaning. There are a lot of people around here who’ve studied them for years and know the stories behind them.”

Debbie Benson, with the Maturango Museum, agreed the emphasis should be on education.

That’s why the festival is being tweaked this year to have more events at Petroglyph Park that include docents giving talks about the history of the area. Benson said she’s reached out to one member of the Paiute-Shoshone and will be reaching out to Bancroft as well.

She added that the museum has an archaeologist on staff and works with an anthropology professor at Cerro Coso Community College to provide educational programs for local school children about the petroglyphs.

“There will be some changes this year,” she said. “We would like the festival to go more in the direction of understanding, respect and the need for preservation.”

If you go

Getting on a tour isn’t easy.

You have to go through the Maturango Museum in Ridgecrest for a supervised tour.

Start at the museum website: http://maturango.org.

Cost is $55 per person for non-museum members.

The museum only has tours in the fall and spring when the weather allows.

Little Petroglyph Canyon is on the Navy base, which allows the Museum to lead a couple dozen regular tours a year under very tightly controlled circumstances. The Navy has opened that up a little for Ridgecrest’s Petroglyph Festival.

Because the petroglyphs are on a military base, visitors going on the regular museum tours must fill out a slew of forms, submit to a background check and, on the day of the tour, all vehicles are searched.

Normally, non-U.S. citizens are not allowed on tours but an exception is made during the Petroglyph Festival.

The regular tours start at the museum at 6 a.m.

The drive from the entrance of the base to Little Petroglyph Canyon, also known as Renegade Canyon, is about 40 miles.

Tours typically last from about 10 a.m. to 2 or 3 p.m.

The canyon itself is only about one and a half miles long so, if you go the whole way, it’s only a three-mile walk.

The terrain is very easy with no steep climbs. The canyon floor is sandy with a few rocks, and there are a couple places you have to scramble down some boulders.

Guides are there to help you. And you don’t have to go the entire way. There is plenty to see on just about every surface.

There are still a few spaces available on tours June 4 and 5.

After that, you’ll have to wait until the fall.