The backstory of a water scare you never knew about

LINK to original story: http://www.bakersfield.com/columnists/lois-henry-the-backstory-of-a-water-scare-you-never/article_e2413d84-4ee7-5bce-9e23-bec87dfcc712.html

- By lhenry@bakersfield.com

-

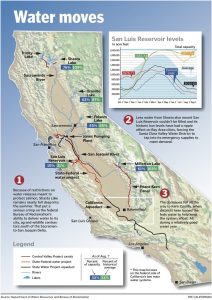

How water in Lake Shasta moves through the delta to San Luis Reservoir and on down to Kern users – or NOT, as happened in summer 2016.

Millions of Californians nearly had their water shut off late last month because the federal government ran out of water — sort of.

Yes, you read that right.

The federal Bureau of Reclamation ran out of water in the San Luis Reservoir and sent shutoff alerts (giving three days notice) to 26 districts it serves in the northern San Joaquin Valley and Bay Area.

One of those was the Santa Clara Valley Water District, which provides water to about two million customers including a few companies you may have heard of such as Apple and Hewlett Packard.

The shutoffs were narrowly avoided thanks, in part, to some quick water trades courtesy of the Kern County Water Agency and Arvin-Edison Water Storage District.

Still, San Luis Reservoir is at historic low levels. Dangerous lows, in fact.

And none of it should have happened at all, say water managers.

Because Lake Shasta is full to the brim.

Yes, you read that right, too.

The feds have heaps of water. Just not in the right place.

That, and other water maneuvers by the Bureau, have water managers up and down the state fuming that regulators’ overly strict operation of the federal Central Valley Project (CVP) has been so reckless it could cause problems years into the future.

HOW THE PLUMBING WORKS

To understand how this near-shutdown happened and why water managers are so worried for the future you have to understand the Central Valley Project (CVP).

Don’t be scared! We’ll take baby steps.

The CVP is the federal side of California’s two biggest water systems. The other is the State Water Project, which we will mostly ignore in this story.

To start, I want to make it clear this isn’t a “fish versus farms” rant. Though the Endangered Species Act is the underlying factor for how this all unfolded.

I’m just fascinated by how turning a valve — or not — 500 miles away can wreak havoc throughout the entire system.

So, here’s what happened.

PLAN, NO PLAN

After four years of unprecedented drought, we actually had a decent water year in 2015-2016 (in Northern California, anyway).

The two main reservoirs the CVP relies on, Shasta and Folsom, were full.

The Bureau of Reclamation was able to repay water it had borrowed the previous year and on April 1 told its contractors how much water it would be able to provide.

It promised 100 percent to all its contractors north of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, 100 percent to so-called Exchange Contractors in the northern San Joaquin Valley and 100 percent to wildlife refuges south of the delta.

It also promised 55 percent of contracted allotments to its municipal users in the Bay Area and 5 percent to its west side agricultural contractors (Westlands Water District and a few other districts).

It made those promises based on approval of a so-called temperature plan for Shasta Lake by the National Marine Fisheries Services (NMFS).

Because Shasta is a linchpin in the survival of the endangered winter-run Chinook salmon, regulators have to make sure it has enough cold water to run down the Sacramento River at the end of October.

The temperature plan outlines how much water can be released from Shasta each month to preserve that needed chunk of cold water. Typically, downstream users can expect up to 13,000 cubic feet per second (CFS) a day in the river.

But salmon took a beating these last few drought years so the Bureau and NMFS created a more cautious plan with limits of 9,000 CFS in June, 10,500 CFS in July and 10,000 CFS in August.

With approval by all the regulating agencies, cities made their water supply plans, farmers planted their crops and wildlife refuges let out a sigh of relief after several dry years.

Happy days, right?

Not so fast.

DOWN TO A DRIBBLE

In early May, NMFS became concerned that initial lake temperature readings came in higher than predicted.

It scrapped the original plan and announced what many saw as a draconian reduction in Shasta releases, no more than 8,000 CFS all summer. In fact, June’s releases were cut back to 7,400 CFS at one point.

The announced reduction caused pandemonium among water contractors south of the delta and the Bureau set about re-negotiating the plan.

Compounding reduced supplies from Shasta was salt.

The delta was hit with a “king tide” starting in June that brought more salt from the San Francisco Bay than had been anticipated.

That required the Bureau, along with the state Department of Water Resources (DWR), to push more fresh water out through the delta to maintain water quality for municipal users.

That wasn’t as great a burden on DWR because it’s responsible to provide only 25 percent of that water and its main reservoir, Oroville, isn’t under the same winter-run salmon release restrictions.

Since the Bureau couldn’t increase its supply of fresh water out of Shasta because of NMFS, it had to move as much water out of Folsom as possible while keeping pumping out of its Jones Pumping Plant near Tracy to only a single pump.

The Bureau planned to move nearly 3,000 CFS daily through Jones and into the San Luis Reservoir. That was down to about 800 CFS this summer.

MAJOR WATER DEBT

The dribble coming out of Jones was quickly overmatched by demand, hence, the feds ran out of water in San Luis in about mid-June.

That’s when the borrowing frenzy started.

San Luis is a holding tank for water from both the feds and state.

They park water in San Luis and, from there, it goes to Bay Area cities, San Joaquin Valley farmers, wildlife refuges or all the way to Los Angeles through a variety of canals.

Contractors also store water in San Luis. Some is left over from previous years and some they purchase from third parties and pay a fee to store in San Luis.

That’s where the Bureau started.

In June and early July it took 270,000 acre feet that federal contractors had stored in San Luis, which caused severe howling and a lot of legal saber rattling from districts that had bought water at steep prices last year and paid to have it waiting for them in San Luis.

The Bureau is still working out how to answer those issues, I was told.

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Finally, on June 28, NMFS approved a new plan for Shasta releases, which was basically the old plan.

But the increased releases for June were moot. June had passed.

The Bureau quickly burned through all its borrowed water and needed more.

It put out a call for help to all water contractors.

On July 15, Arvin-Edison, Kern County Water Agency and the state Department of Water Resources stepped up offering water through loans and exchanges.

The feds accepted but weren’t initially able to get the required permits to make the deals.

That’s why, on July 21, the Bureau sent three-day shutoff notices to all its contractors.

That includes the Santa Clara Valley Water District, which was already having to use its emergency water supplies out of Anderson Reservoir to blend with San Luis water because San Luis had dropped so low the water had become too fetid for Santa Clara to run directly through its treatment plants.

WHISTLING PAST THE GRAVEYARD

The Bureau finally got its permits and no one was shut off but it still only had a trickle coming from Shasta, the king tide to deal with and obligations to meet south of the delta.

It had to borrow even more water, all the way from Fresno and at least one Friant Division district.

As the calendar ticks toward mid-August, the Bureau is holding its breath.

That’s because salinity requirements will drop off mid-August, demand from north-of-delta users is expected to relax and NMFS actually agreed to keep Shasta releases at 10,500 CFS per day rather than throttle back to 10,000 CFS as outlined in the temperature plan.

Yes, water managers say, the crisis appears to be coming to a close.

REPAYING THE DEBT

But what about next year?

“The Bureau should be moving as much water south as they can right now (to repay the approximately 380,000 acre feet it owes),” said Ara Azhderian, water policy administrator for the San Luis & Delta-Mendota Water Authority. “But there doesn’t seem to be much opportunity for that this fall.”

Indeed, Ryan Wulff, branch chief for Delta Policy and Restoration with NMFS, reminded me these next few weeks are typically very hot so releases from Shasta will continue cautiously.

And even with this abundance, some say over abundance of caution (water managers tell me Shasta has 325,000 acre feet more cold water than the NMFS plan called for), Wullf predicted this fall’s salmon run will be paltry at best because of previous drought years.

And that, Azhderian said, is one of the most frustrating aspects of all of this.

“We need effective regulation so all these sacrifices actually result in something,” he said. “Part of the problem is we’re a victim of our own success.”

California’s water districts are so adept at moving, trading and exchanging water, the public never really knows how close we come to the cliff edge.

“People don’t have the foggiest idea of how it all works.”

Opinions expressed in this column are those of Lois Henry. Her column runs Wednesdays and Sundays. Comment at http://www.bakersfield.com, call her at 395-7373 or email lhenry@bakersfield.com.

LOIS HENRY ONLINERead archived columns by Lois Henry at Bakersfield.com/henry.

TIMELINEMarch 31 — National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) approves the Bureau of Reclamation’s temperature plan for Shasta Lake. Enough cold water must be kept in the lake to release at the end of October for winter-run Chinook salmon. The plan would have allowed daily releases of 9,000 CFS in June, 10,500 CFS in July and 10,000 CFS in August.

April 1 — Based on NMFS’ approval of the Bureau’s temp plan, the Bureau announces water allocations of 5 percent of contracted amounts for west side ag districts, 55 percent for municipal clients and 100 percent each for wildlife refuges, below delta exchange contractors, above delta Sacramento Valley diverters and Sacramento Valley Settlement Contractors.

Mid-April — Shasta fills to near capacity of 4.3 MAF, Folsom fills 850,000 AF.

April through May — Bureau only runs one pump out of six available in its Jones Pumping Plant near Tracy. One pump moves 800-1,000 CFS of water per day.

May 2 — NMFS rejects the original temp plan as early lake temperatures come in warmer than predicted. NMFS states it will reduce Shasta releases to 8,000 CFS all summer. The Bureau and NMFS enter negotiations for a new plan.

Month of June — Because there is no temp plan in place, NMFS keeps Shasta releases to 7,400 CFS. Bureau quickly begins falling behind in filling San Luis Reservoir, which is used to meet its south-of-delta obligations.

June through July — A “king tide” creates salinity issues in the delta, forcing the Bureau and state Department of Water Resources (DWR) to push 8,000 to 12,000 CFS per day to the ocean through releases from Folsom and Oroville. Typically, the agencies would have to move 7,500 CFS through the delta for salinity.

Mid-June — Bureau has no water in San Luis Reservoir and is forced to borrow 270,000 AF from federal contractors who had stored water there from previous years or who had purchased water from third parties and stored it in San Luis. That water is used to meet the Bureau’s April allocations but only lasts until mid July.

June 28 — NMFS agrees to a second temp plan that allows for releases of 9,000 CFS in June (but June has passed), 10,500 CFS in July and 10,000 CFS in August.

July 6 — Santa Clara Valley Water District is forced to tap its emergency supplies at Anderson Reservoir to blend with water out of San Luis because the San Luis water had become fetid as lake levels dropped dramatically. Santa Clara has used 12,000 AF of its emergency supplies.

July 15 — The Bureau is again out of water in San Luis. It asks for help from all contractors including those on the State Water Project. It inks a deal to borrow 12,000 AF from Arvin-Edison Water Storage District, a Friant contractor,* and exchanges 45,000 AF of federal water from Millerton with the Kern County Water Agency, a state contractor. The Bureau also borrows 38,000 from DWR. But it needs approval from the State Water Resources Control Board to make those trades.

July 21 — The Bureau doesn’t get approval and sends shutoff notices to 26 water districts alerting them pumping would cease in three days.

July 22 — Shutoff is narrowly avoided after an all-night session between Bureau and Water Board employees results in the needed approvals.

July 22 — The Bureau approves an increase in allocations to contractors on the Friant side of the CVP, which takes water from Millerton, igniting a firestorm of criticism from other federal contractors who were still in danger of being shut off.

July 22 — Westland’s Water District agrees to take 40,000 AF of water it had purchased and stored in San Luis as an emergency stash, rather than what was promised by the Bureau in April. It also gives 5,000 AF from that emergency stash to San Luis Water District.

July 25 — Bureau borrows another 10,000 AF from Fresno Irrigation District and the City of Fresno and sends it down the San Joaquin River from Millerton for west side ag contractors.

Aug 1 — Bureau borrows another 5,000 AF from a Friant district to send down the San Joaquin from Millerton for west side contractors. Total borrowed, not including Westlands water, is 380,000 AF.

Aug. 1 — At 205,000 AF, San Luis Reservoir is lower even than it was in 1976-77, one of the driest years on record.

Aug. 10 — NMFS agrees to keep Shasta releases 10,500 CFS daily through August rather than dropping down to 10,000 CFS as planned.

Future — There are no certain plans for how the Bureau will repay the 380,000 AF it borrowed.

West side federal contractors believe the debt should be paid out of Millerton.

Friant division contractors (which include several districts in Kern County) believe the water should be repaid through increased pumping out of the Jones facility this fall.

Either way, all sides are hoping this debt doesn’t reach into the 2017 water year.

*The CVP south of the delta is split into two halves. One serves districts in the Bay Area and along the west side of the valley, the other serves districts in the Friant Division, which includes Arvin-Edison, Shafter-Wasco Irrigation District and Kern Tulare Water District in Kern County.