Lost to history: H.H. and undercover Land Co. saga

- LINK to original article: http://www.bakersfield.com/columnists/lois-henry-lost-to-history-h-h-and-undercover-land/article_76544036-f747-51b6-afb7-e91273401351.html

- By LOIS HENRY, The Bakersfield Californian lhenry@bakersfield.com

Let’s see, last I left you, “Operative H.H.” had made inroads into Bakersfield society and was preparing to head out into the countryside to look for the nefarious hay-burning gang.

If you have no idea what I’m talking about, no worries. Let’s catch you up from Part 1 last week.

Thanks to Kern County Museum Curator Lori Wear, I came across a great piece of local history filled with intrigue and funny turn-of-the-century writing.

Back in August 1891, some angry locals set fire to 10 haystacks belonging to the Kern County Land Co. These haystacks were bigger than most houses at the time — and no hay meant no feed for Land Co. cattle. It was also an indication of how despised the Land Co. was as it gobbled up more and more land (and water) through both legal and nefarious means. And when I say the Land Co. was despised, I mean really hated.

Local historian Gilbert Gia has written about how one of the Land Co.’s lawyers was arrested, shot, tarred and feathered in 1890 (just a year earlier) for his antics in getting people’s land by hook or crook. If the Land Co. couldn’t buy a settler out, or trick his land out from under him, it would, apparently, send lawyers to the court up in Visalia to make a claim on the land. The settlers would have to get up to Visalia to defend their claim and often found the case was postponed or canceled, only to be filed again at a later date. One woman even claimed Land Co. agents dumped dead dogs down her well to force her off her land, according to Gia.

So burning Land Co. hay was probably cheered by a lot of good Kern County folks of the day.

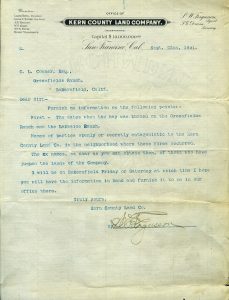

For its part, the Land Co. did not take the offense lightly. It hired a San Francisco detective agency to track down the wrong doers.

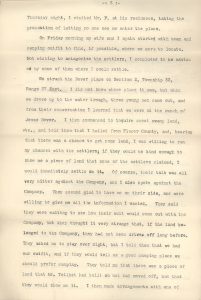

What Wear found were reports from that agency’s man on the ground, known only as “Operative H.H.”

H.H. took the train down from San Francisco with his wife, bought a buggy, a team of horses and camping equipment in Fresno and proceeded to Bakersfield where he pretended to be a hayseed looking for land. In his Oct. 4 report, H.H. notes that several real estate men had little good to say about the Land Co. He had also met with a Mr. Maude, most likely A.C. Maude, who sold land, dabbled in insurance and owned the Daily Californian , which railed against the Land Co. on a regular basis.

H.H. has a list of names of those suspected of burning the hay stacks. He’s eager to get out into the community and its ranches to find these fellows and pin down this case.

His next report is Oct. 11, 1891.

The Sells Bros. Circus was in town and H.H. attended with Mr. Maude.

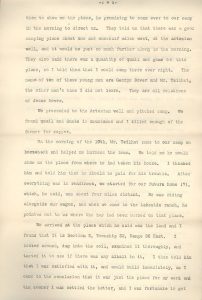

“He talked considerably about land and stated that ‘the Company had a kind of hold on him,'” H.H. reports. “But he did not say what it was, nor did I ask him.”

Maude repeatedly tells H.H. not to talk about the Land Co. in front of others.

“… for the reason that I might want a piece of land and have to get water from them, and that some of the hirelings of the Company would inform the office, and they would make it very bad for me.”

Later that week, H.H. and his wife take the buggy out at night to map roads near the land he’s supposedly interested in homesteading “so in an emergency I could slip up to town in the night and avoid the settlers” presumably so he can report back to his agency without suspicion.

After a clandestine meeting with Ferguson, H.H. and his wife make their way toward the ranch of one of the suspects, Jesse Dover. H.H. meets several of Dover’s relatives at the ranch and befriends the group.

“Of course, their talk was all very bitter against the Company, and I also spoke against the Company. They seemed glad to have me on their side … They said they were waiting to see how their suit would come out with the Company.”

That may be a reference to a lawsuit filed against the Land Co. that resulted in the Shaw Decree of 1900.

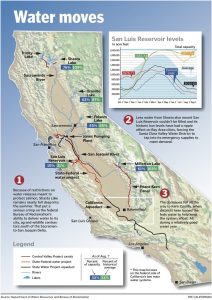

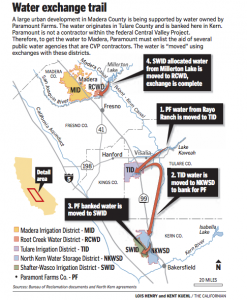

The Kern River had already been divided up, basically, between the Land Co. and Henry Miller, in a landmark 1888 case that created the basis of California water law regarding riparian versus appropriative rights. But that lawsuit neglected to take into consideration the rights of many long standing ditches that had pulled water from the Kern River for years. The Shaw Decree assigned rights to those ditches, which remain in use today.

Back to 1891.

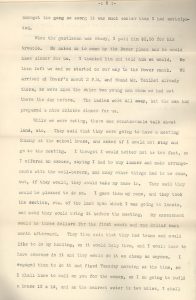

The Dover ranch folks helped H.H. find a camping site and one of them, Mr. Teilhet, even helped hitch up his team and gave H.H. a tour of the area.

“He was riding alongside our wagon, and when we came to the Lakeside ranch, he pointed out to us where the hay had been burned on that place,” H.H. writes of Mr. Teilhet.

H.H. pretends to like the land he’s shown and says he’ll settle it right away.

“I was fortunate to get amongst the gang so soon; it was much easier than I had anticipated,” he reports.

The Dover ranch folks later give H.H. and his wife a “nice chicken dinner” and invite him to a meeting about land issues.

“I thought I would better not be too fast,” H.H. writes and begs off.

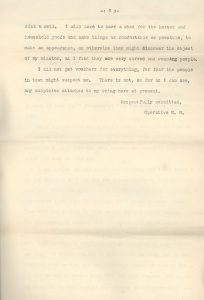

What’s fascinating is how H.H. intends to actually sink a well, build a house (12 by 14) and horse shed all to “make an appearance, as otherwise they might discover the object of my mission, as I find they are very shrewd and cunning people.”

He ends by saying: “There is not, so far as I can see, any suspicion attached to my being here at present.”

Did H.H. discover the hay burning culprits?

Did the Land Co. make them pay?

Or did H.H. perhaps join in with the “shrewd and cunning” bunch, sink that well and go into farming?

We will never know.

Sadly, that’s the last report Wear could find in her archives.

Though the outcome may be lost to history, this small snippet is wonderfully instructive of the age-old connection between water, land and money.

A connection just as powerful, and meaningful, today as it was 123 years ago.

Contact Californian columnist Lois Henry at 395-7373 or lhenry@ bakersfield.com. Her work appears on Sundays and Wednesdays; the views expressed are her own.