http://www.bakersfield.com/special-sections/take-our-river-back/2010/05/06/lois-henry-river-divides-agency-city.html

When the City of Bakersfield bought its extensive water rights to the Kern River more than 35 years ago, it was a defensive move no one ever thought would be needed.

A brimming aquifer and river flowing through town made water a non-issue for Bakersfield. The city always had enough, more than enough in some years.

Then in the late 1950s and early ’60s, things changed. Groundwater levels dropped, wells had to be deepened regularly and the river went dry. Not unlike today.

City leaders began a years-long investigation to find out where our water had gone.

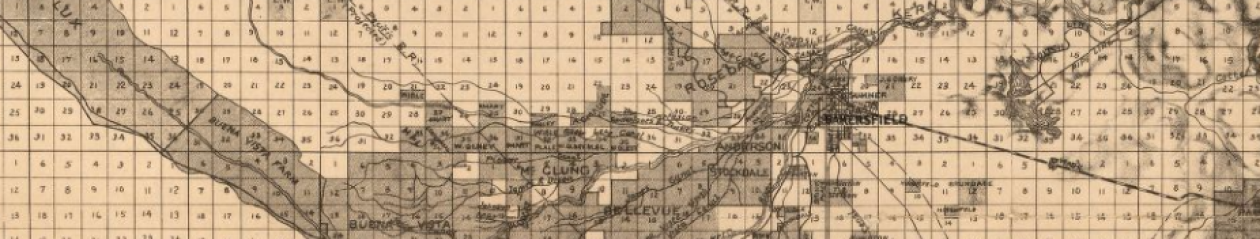

Bakersfield had never been a party to the deal-making and lawsuits on the Kern River. Instead, powerful ag interests divvied up the river amongst themselves.

The city found its river, and the groundwater it supplied, had gone to support vast farming empires, sometimes on far-flung lands.

Weirs upstream were taking bigger and bigger bites of the river. More groundwater was being pumped out from under the city for new ag lands.

And Tenneco West (the successor to the Kern County Land Company) had built a concrete-lined canal to deliver water west of town that was depriving the city of even that amount of percolation.

The city’s water and its implicit right to Kern River water was, literally, being pumped away.

Getting the water back

City leaders tried to negotiate with Tenneco but got nowhere.

So they filed several lawsuits asking the courts to, among other things, determine the river’s ownership, declare that the city had rights to the water and stop ag interests from taking more water than their rights.

Tenneco settled by selling all its rights and facilities to the city for $17 million, giving Bakersfield rights to an average 160,000 acre feet a year of pristine Kern River water.

In order to pay off that $17 million, Bakersfield locked up 70,000 acre feet a year of its river water in long-term contracts with several agricultural water districts. Those contracts are up in 2012.

The rest of the water has been used to accommodate growth, bank for dry years and sold to other local ag districts as requested.

Even with its Kern River rights, though, Bakersfield’s groundwater levels have dropped drastically in the last three years and the river, again, is dry.

Almost back where we started

With the city’s river water tied up in ag contracts, it hasn’t had extra for the river channel. And even after the 2012 contracts come due, that water is slated for future growth. The city could run some down the river while housing is still in a slump, but it will eventually go to growth.

That’s why the city is seeking ownership of 50,000 acre feet of river water forfeited by an ag district in 2007. The city has vowed to keep that water in the river.

Other water districts, including the Kern County Water Agency, are also seeking that 50,000 acre feet of water, for irrigation and unspecified municipal uses.

The Agency and the city have long had a tense relationship so this latest face-off should come as no surprise.

The city is still upset over an agreement for the Agency to put water in the river to recharge the aquifer in exchange for having levied pump and property taxes (about $5 million a year) on Bakersfield residents over the last 30 odd years.

Agency General Manager Jim Beck said the Agency has run water down the river when possible. But the drought, state water reductions and added demands for treated water have made that impossible.

The city disputes Beck’s arguments, saying the Agency has had extra water even during the drought that hasn’t gone in the river or has only run east of Manor Street.

Either way, the outcome is a dry river.

Water flows toward money

Meanwhile, the rate of groundwater depletion isn’t explained merely by the recent drought and lack of water in the channel.

Groundwater levels have dropped 150 feet in some areas, said Tim Treloar, manager of California Water Services, Bakersfield’s main private water purveyor.

The drop is steadily moving east as Kern’s major water banks at the western end of the Kern River suck out more water.

In other, even worse, dry spells, farmers pumped more groundwater, but a lot of it made it right back into the aquifer when it was spread on local fields.

Some of Bakersfield area groundwater is going to westside farmers because of reductions in state water. That basin doesn’t connect to ours, so the water is lost.

But the big difference is that a lot of our groundwater is going over the Grapevine to Southern California cities.

“It shouldn’t be happening this fast if it were only going to local ag,” Treloar said.

Several city and Cal Water wells have already had to be shut down as water quality has worsened because of declining supplies.

Eric Averett, General Manager of the Rosedale Rio-Bravo Water Storage District, said his district, which relies solely on groundwater and is right next to two major water banks, is being hit hard.

Some Rosedale landowners have had wells go dry, Averett said.

Showdown looming

Members of the Kern Fan Monitoring Committee, made up of the water bank representatives, have promised to study the problem.

Agency General Manager Beck said it would be a year or two before data is available from the study. That could be too late for some areas.

The Agency operates the Pioneer Project and is a partner in the Kern Water Bank.

A report done by Rosedale Rio-Bravo a few years ago showed, among other things, that the Kern Water Bank was pumping out more water than it needed and that it hadn’t put as much water into the bank as it had claimed.

Jonathan Parker, manager of the Kern Water Bank Authority, disputed those findings. Beck said he hadn’t seen the report.

The argument could be headed to a courtroom sometime soon.

All of which makes the 50,000 acre feet of forfeited water the city wants to run down the river to replenish our groundwater “huge, really huge,” Treloar said.

Back in the ’70s, Cal Water joined the city in its lawsuits against Tenneco West.

Just like a lot of things on the river, not much has changed over the years.

“We’re joined at the hip with the city on this issue,” Treloar said. We’re all in.”